This isn’t my coming-out story (but it is my battle cry)

On the Institute for Sexual Science and Contemporary Politics of Erasure

i. Introduction

When I began hormones in March 2023, I thought it would be a quiet transition… something private, medical, almost mundane. Instead, it detonated my life. Within months I was divorced, my family drifted into silence, and most of my old friends vanished. When Trump won again in November 2024, I walked into work and said it out loud: I’m a trans woman, and I’m not hiding anymore.

The room didn’t explode. There were polite smiles, a few averted eyes looking at my skirt and presence in a different bathroom. But something shifted; I had crossed from plausible deniability into visibility. Since then I have lived in the open, and living in the open is its own form of peril. Every morning, before I even touch the door handle, I perform a calculation who might stare, who might follow, who might decide that my existence invites comment or correction. And still, I keep stepping outside. To disappear again would be another kind of death.

Visibility is not freedom, but it is proof. Proof that we are still here, proof that erasure has failed. It’s why I write at all: to keep a record, to leave something unburnable.

Wherever they burn books, they will end in burning bodies -Heinrich Heine

A Brief History of the First Reckoning

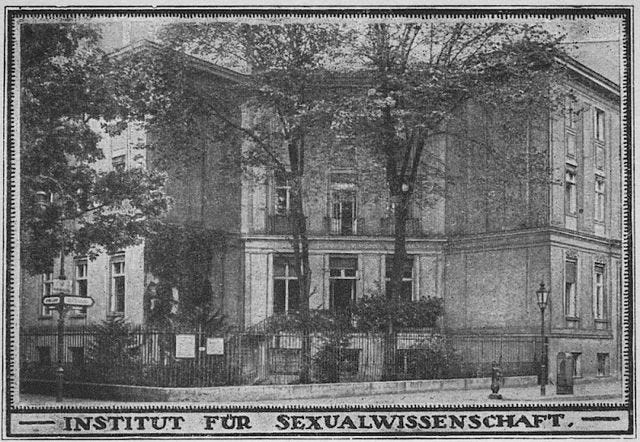

More than a century ago, another generation of queer people reached for that same proof. In 1919, Berlin opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (the Institute for Sexual Science) founded by the German physician Magnus Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish doctor, believed that scientific understanding of sexuality could lead to justice. He etched that faith into the Institute’s motto: Per Scientiam ad Justitiam (through science to justice, Beachy, 2014).

Hirschfeld had already spent decades fighting Germany’s anti-sodomy law, Paragraph 175. In 1897 he formed the Wissenschaftlich-Humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), the world’s first organization devoted to LGBTQ rights (Steakley, 1976). He and his colleagues circulated petitions for repeal signed by cultural heavyweights like Einstein, Rilke, and Thomas Mann. Their argument was revolutionary: same-sex love and gender variance were not crimes or sins but natural variations of humanity.

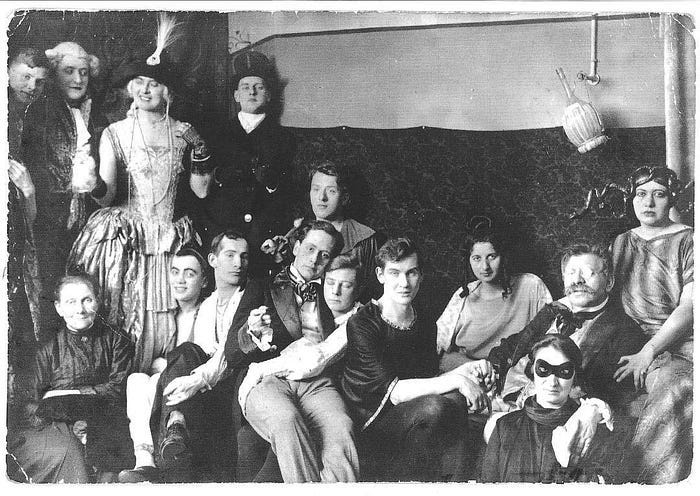

By the time the Institute opened, Berlin was a laboratory of possibility. The Weimar Republic legalized some forms of birth control, allowed relative freedom of the press, and permitted cabarets to mock authority. Queer magazines such as Die Freundin and Das Dritte Geschlecht circulated in the open, and more than a hundred gay and lesbian bars thrived (Isherwood, 1976). Christopher Isherwood later wrote that Berlin “seemed to know everything that could happen to you, and yet not care.”

Inside the Institute, Hirschfeld and his colleagues catalogued the full spectrum of human desire. They offered counseling, contraception education, medical exams, and, crucially, gender-affirming care long before the term existed. Patients who today might identify as trans could live at the Institute, receiving hormones, therapy, and sometimes surgery. Hirschfeld’s research coined early concepts of transvestism and transsexualism, laying groundwork that modern sexology still builds on (Marhoefer, 2015).

Among the staff was Dora Richter, a domestic worker who began transitioning in 1922 and later underwent full genital reconstruction and was the first recorded woman to do so (Dose, 2018). Another patient, Lili Elbe, would follow in the early 1930s, her letters later inspiring The Danish Girl. The Institute became a haven for people who had never before seen themselves reflected anywhere.

The Promise and the Precarity

The world surrounding Hirschfeld was fragile. Germany after World War I was humiliated, economically shattered, and searching for scapegoats. Conservatives called Berlin’s new freedoms a “moral collapse.” Reactionary newspapers singled out Hirschfeld’s work as evidence of national decay, calling his Jewishness and his sexuality twin corruptions (Plant, 1986). The Institute was attacked repeatedly: windows smashed and staff beaten. It endured, publishing monographs, hosting lectures, and treating thousands of patients from across Europe.

Reading those histories, I think about how modern trans clinics operate under similar siege: protests on sidewalks, threats to doctors, legislation aimed at shutting them down. The parallels aren’t rhetorical; they are procedural. Moral panic always begins with the claim of protecting society from the “unnatural,” and it always ends by deciding who gets to live.

For a brief, brilliant decade, the Institute embodied the possibility of a humane world. Its very existence answered the question of whether a society could accept sexual and gender diversity: yes, it could. And then it didn’t.

ii. What they burned, we rebuild

The end came fast. In the early months of 1933, the Nazi Party consolidated power. Berlin’s queer nightlife, its bars, magazines, drag balls, became the first targets of “moral cleansing.” The same newspapers that had mocked Hirschfeld for decades now called openly for his arrest.

On May 6, 1933, students affiliated with the Deutsche Studentenschaft (the Nazi Student Union) marched on the Institute for Sexual Science. They broke down doors, carried away cabinets of patient records, and looted everything that could be moved. Four days later, they piled the books and archives in a public square at Opernplatz, doused them in gasoline, and set them alight. One estimate says that between 12,000 and 20,000 books and journals, nude images of sex subjects, and other items were destroyed. These included artistic works, rare medical and anthropological documents, charts concerning cases of intersexuality, and more. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda, watched from a podium as the flames climbed into the night. He later told the crowd that Germany would “cleanse itself of Jewish intellectualism” (Marhoefer, 2019).

Eyewitnesses said a bronze bust of Hirschfeld was thrown onto the pyre. Photographs show students saluting as pages turned to smoke. Inside those pages were the first case studies of trans women, the first clinical data supporting homosexuality as innate, the first detailed surgical reports of gender-affirming operations. Until recently, historians thought Dora Richter was killed during the raid; her name disappears from most records afterward (Plant, 1986). It was later revealed that she left Ryzovna and ended up in Allersberg, Germany, from 1946 until her death on April 26th in 1966 (Lili Elbe Archive, 2024).

When I look at those photos, I think about how fragile knowledge is and how easily an idea can burn. The destruction of the Institute wasn’t a symbolic act; it was genocide in paper form. The Nazis targeted queerness and Jewishness together, conflating both with “degeneracy.” They wanted to erase not only people but also the language that had allowed those people to describe themselves.

Magnus Hirschfeld, watching from exile in France, saw newsreel footage of the bonfire. He died two years later on his 67th birthday. The Institute’s motto, through science to justice, died with him, at least for a time (Wolff, 1986).

After the Ashes

The war ended, but silence replaced fire. The Allied powers did not rush to restore queer rights; they preserved the same laws that had condemned Hirschfeld’s patients. Paragraph 175, the statute criminalizing male homosexuality, remained in force in West Germany until 1969. In East Germany, it lingered even longer (Bundesarchiv, 1969). Survivors of concentration camps were not recognized as victims. Many were re-arrested after liberation and sent back to prison to finish their “sentences.”

The post-war decades produced a paradox: the West celebrated freedom while pathologizing desire. American psychiatry classified homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance in the DSM-I (American Psychiatric Association, 1952). Gender variance was folded into “sexual deviation.” Science, once a tool of liberation, became an instrument of control.

Hirschfeld’s ideas survived only in fragments such as footnotes, citations, and whispered acknowledgments. A few researchers abroad picked up his trail. In the United States, Alfred Kinsey’s work on sexual behavior in the late 1940s drew indirectly from German sexology. Kinsey’s team corresponded with émigré scientists who had fled Berlin, inheriting both their data and their defiance (Katz, 1995).

Still, the larger culture wanted amnesia. Queer people were purged from government jobs during the Lavender Scare in 1953. Trans women like Christine Jorgensen were treated as curiosities on talk shows, their bodies dissected by journalists in tones of fascination and disgust.

The Long Silence and the First Echoes

By the 1970s, two parallel revolutions began: gay liberation and the second-wave feminist movement. Stonewall’s riots in 1969 marked a turning point, but the memory of earlier generations was mostly gone. Few activists in New York or San Francisco knew Hirschfeld’s name. The archive had burned; oral history could only reach so far.

When I first read about those lost years, I felt the grief of repetition. History doesn’t just repeat. It refolds. Each generation fights the same battle in a different key, with slightly altered instruments. The enemies change costumes; the language of purity remains.

The 1980s brought the HIV/AIDS crisis, another moral panic that fused disease with identity. Governments again ignored science in favor of ideology, letting thousands die. In the United States, Ronald Reagan said nothing publicly about AIDS until 1985, by which time more than 12,000 Americans were dead (Shilts, 1987). Hirschfeld’s dream that science might deliver justice felt impossibly far away.

During those years, historians and archivists began to reconstruct what had been lost. In Berlin, surviving colleagues of Hirschfeld formed the Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft in 1982, dedicated to preserving his work. By 1984, they had located fragments of correspondence, partial case notes, and several hundred surviving photographs (Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft, 2018). Later, the Schwules Museum in Berlin devoted a permanent exhibit to the Institute’s memory, describing it as both “a monument and a warning” (Schwules Museum, 2022).

That act of reconstruction matters because archives are not neutral. They are maps of what a society wants to remember. Every record that survived the fire undermines the myth that queerness is new, that trans women appeared out of nowhere.

iii. Through visibility to justice

The lesson of the Institute’s destruction should have inoculated the world against forgetting. Instead, we reenact it with new technology. When school boards pull queer authors from library shelves, when states outlaw medical care for trans teens, when digital platforms quietly demote content about transition, the bonfire simply burns in code rather than kerosene. Erasure has gone algorithmic.

In 2025, more than a hundred anti-trans laws have passed in the United States (Trans Legislation Tracker, 2025). They target bathrooms, sports teams, healthcare, and even the words teachers can say in classrooms. Each one is presented as moderation: “protecting children,” “preserving fairness.” That was exactly the rhetoric used in Weimar’s collapse: the moral panic that demanded cleansing.

What unsettles me most is how familiar the cadence sounds. I hear it on talk shows, in campaign ads, even at the grocery store checkout when strangers debate “what to do about people like that.” The language of eradication has become background noise. And I, living proof of what they want gone, still have to go to work, still have to buy food, still have to keep my head high at the register.

When commentator Michael Knowles told a cheering CPAC audience that “transgenderism must be eradicated from public life,” I felt something cold settle in my chest. That word eradicated wasn’t chosen by accident. It was the same vocabulary Goebbels used to describe ideas he found intolerable (C-SPAN, 2024). The difference is only one of media format: now the flames are broadcast in HD.

The Personal Present

After my surgery in June, I woke in a room flooded with pale light and the smell of antiseptic. My throat ached from anesthesia; my body ached from history. Lying there, I realized the procedure wasn’t just medical. It was archival. Every trans person writes a new footnote in a book that others keep trying to burn.

Since starting this journey in 2023, I’ve been groped, followed, stared at, photographed without consent. I’ve had people look over my bathroom stall, trying to confirm that I wasn’t the same as them. I’ve been followed by a man in a car asking me to get in. I’ve been told I’m brave, and I’ve been told I’m delusional. Sometimes the same person says both. But even on the worst nights, when fear hums in my blood, I remember that invisibility is what made the last century’s fires possible. Visibility, dangerous as it is, remains the only antidote.

I didn’t choose this life because I wanted to be exceptional or draw negative attention. I chose it because I wanted to be real. Authenticity has a body count, but it also has a lineage: Dora Richter, Lili Elbe, Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, every woman who stood in the street and refused to move. Their defiance built the ground I’m standing on.

Rebuilding the Institute

If Hirschfeld’s institute taught anything, it’s that progress depends on memory. The scientists and activists rebuilding its archive today, Laurie Marhoefer, Ralf Dose, the team at Berlin’s Schwules Museum, are doing more than history; they’re resurrecting evidence (Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft, 2018; Schwules Museum, 2022). Each recovered letter, each photograph, is an argument against the lie that queerness is a modern fad.

In a way, the Institute already exists again distributed across servers, message boards, and discord chats. Mutual-aid networks share HRT information, legal advice, and housing leads. Archivists digitize zines and oral histories. None of this can be raided in a single night. What Hirschfeld once centralized, we’ve decentralized hopefully beyond destruction.

Science remains part of the fight, but compassion is its missing twin. The data proving that gender-affirming care saves lives is abundant (Mallory et al., 2024). What’s scarce is the willingness to listen. Hirschfeld believed knowledge would be enough; experience tells me empathy is the harder revolution.

Faith, Politics, and the Old Scripts

I grew up in an evangelical household where queerness was treated as both tragedy and temptation. Sermons warned that “the world” wanted to steal our moral birthright. Now that same theology fuels policy. Watching it happen feels like déjà vu: the fusion of religion and nationalism, the sanctification of cruelty.

But faith itself isn’t the enemy. Hirschfeld never renounced spirituality; he simply refused to let it define truth. He saw scientific inquiry as a moral duty. In that sense, every trans person who documents their life continues Hirshfeld’s work. We turn existence into evidence.

The Cost of Survival

Living openly is expensive. It costs family, safety, sometimes love. But each day that I exist publicly, another trans person might glimpse possibility. Someone might see me wearing a skirt at Target, someone might see me in the drive-through ordering food. That is enough to keep me going. Visibility isn’t pride-month marketing; it’s the light by which someone else can navigate their own darkness.

I know the risk. I’ve lived it. Yet every morning I choose to walk out the door in the body that almost killed me to claim, because I believe that safety built on silence isn’t safety at all.

Through Visibility to Justice

When I stand under Denver’s morning-orange sky, I imagine Hirschfeld walking home along the Spree after a long day at the Institute, unaware that the fire was coming. I think of Dora Richter, of the nameless others whose files turned to ash, of all the data points erased from the human record. They weren’t just victims; they were the first witnesses.

Their legacy isn’t the tragedy of loss but the insistence on documentation and the belief that if we record ourselves thoroughly enough, maybe next time the fire won’t take everything. That’s what I’m doing now. Every essay, every poem, every photograph, every public moment is an entry in a living archive.

I am not writing a coming-out story. I am writing a survival manual. I am writing proof. The motto above the Institute’s door still stands: Through science to justice. I’m updating it for our era: Through visibility to justice. Because without witnesses, there is no science, no truth, no freedom.

I am Morgan Voisin. I am a trans woman. I’m out everywhere. And I will not let them look away.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (1st ed.). Washington, DC.

Beachy, R. (2014). Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a modern identity. New York, NY: Knopf.

Bundesarchiv Germany. (1969). Paragraph 175 and its repeal [Archival dossier].

C-SPAN. (2024). CPAC 2024 transcript: Speech by Michael Knowles. Washington, DC.

Dose, R. (2018). Dora Richter (1892–1933?). Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft Archives.

Isherwood, C. (1976). Christopher and his kind. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Katz, J. N. (1995). The invention of heterosexuality. New York, NY: Dutton.

Lili Elbe Archive. (2024, September). Dora lived. Retrieved from https://lili-elbe.de/blog/2024/09/dora-lived/?ref=wearequeeraf.com

Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft. (2018). Reconstruction project documents. Berlin, Germany.

Mallory, C., Brown, T. N., & Sears, B. (2024). The impact of 2024 legislation on transgender youth. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

Marhoefer, L. (2015). Sex and the Weimar Republic. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Marhoefer, L. (2019). 90 years on: The destruction of the Institute of Sexual Science. JSTOR Daily.

Plant, R. (1986). The pink triangle: The Nazi war against homosexuals. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Schwules Museum Archiv Berlin. (2022). Permanent exhibit: The Institute for Sexual Science. Berlin, Germany.

Shilts, R. (1987). And the band played on: Politics, people, and the AIDS epidemic. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Steakley, J. D. (1976). The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Journal of Homosexuality, 1(4), 303–329.

Trans Legislation Tracker. (2025). Anti-trans bills 2025. Retrieved from https://translegislation.com

Wolff, C. (1986). Magnus Hirschfeld: A portrait of a pioneer. London, England: Quartet.

Author’s Note

Writing this piece was not an act of nostalgia. It was an act of survival. It’s a continuation and re-writing of an essay I did when I started HRT in 2023.

Every draft hurt a little, because the history of Hirschfeld’s Institute is not ancient history; it’s a mirror. When I read about the students who dragged those books into the fire, I see the same impulse that still flickers in comment sections and statehouses. They wanted to erase the evidence that people like me existed.

I am here to be evidence. I write these words in a body that medicine once called impossible, in a world that keeps insisting it would be easier if I disappeared. But I am still here, and I am still writing.

If you have ever felt the heat of that fire, if you have been told that your life, your love, your gender are theories to be debated, know that you are part of the same archive. We are rebuilding the Institute every time we tell the truth about ourselves.

This essay is dedicated to those who didn’t survive visibility, and to everyone still learning how to live in it.

I appreciate this essay, it gives a hopeful message that one cannot get from simply reading wiki articles.