She was the Portal

Everworld, Senna, and the Trans Allegory That Wasn't

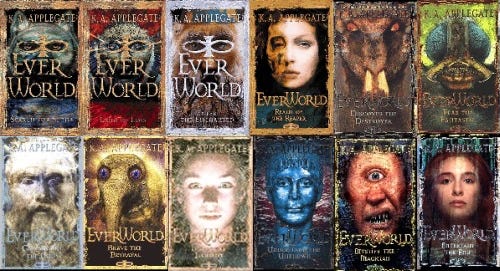

Introduction: The Girl on the Safeway Shelf

I was twelve years old the first time I saw her. The cover was worn, nestled between gum racks and celebrity tabloids at a Safeway checkout line. Everworld: Search for Senna. I didn’t know what the book was. I didn’t know who Senna was. But I picked it up anyway. I took her home.

What I didn’t know then was that I was carrying a mirror.

At the time, I didn’t have the language for what I was feeling. I didn’t know I was transgender. I didn’t know that one day I’d start hormone therapy, come out, undergo surgery. I didn’t even know what trans meant. I only knew that something about Senna haunted me, and thrilled me. She was beautiful. She was dangerous. She was feared, powerful, and not exactly loved. And she was always just out of reach. Always vanishing into another world.

Senna was the first time I saw a girl I felt like.

This essay is a reflection on that feeling, and how the Everworld series, unintentionally, became a transgender story for me… not in its literal events, but in its emotional architecture. This isn’t a literary critique so much as it is a memory: of what it meant to escape, to be split between two worlds, to feel wrong in one and right in another, and to survive long enough to become something real.

Part I: What Is Everworld?

Everworld, written by K.A. Applegate and published between 1999 and 2001, is a twelve-book fantasy series following four teens, David, April, Jalil, and Christopher, who are pulled into a parallel universe by a girl named Senna Wales. Everworld is a place where gods, monsters, and myths are alive, colliding in an ongoing war for control. Time functions differently there. Rules of physics bend. And for the kids who enter it, the experience is violent, disorienting, and often irreversible.

The central character, in many ways, is not any of the four narrators, but Senna. The story begins and ends with her. She is the portal, both literally and figuratively. Senna is the reason the protagonists are dragged into Everworld, and her power (mysterious, magical, feminine) is the engine behind much of the plot. She is described alternately as a witch, a goddess, a manipulator, and a threat. The boys want her. The girls fear her. The world bends around her. And by the end of the series, she becomes both martyr and monster, consumed by her own mythos.

The books were not written as a trans allegory. And yet.

Part II: The Duality of Worlds

Reading Everworld at twelve felt like splitting open. There was here, and there was there. Here was school, family, pressure, the growing dread of boyhood pressing in on me like a closing box. My voice was changing, my dad wanted me to learn about working on cars, the boys at school started lifting weights. And there… there was Everworld. A place where fear and violence lived openly, but so did magic. A place where transformation wasn’t just possible; it was required.

The idea of being stuck between two worlds, of being pulled without consent into a place that feels more real than the one you came from, became my private metaphor for gender. The real world, the one everyone agreed was real, had no room for me. I didn’t even have the words to say what I was. But I felt it.

And when I read Everworld, I felt less alone in that fracture.

In the books, the protagonists live double lives. In the real world, their bodies go limp while their Everworld selves are pulled into danger. They suffer in both places. Their memories don’t always align. Their identities blur. There is no way to choose one world fully; they are bound to both.

This is what being closeted felt like.

In my teenage years, I lived as a boy. Everyone thought I was one. I played the part awkwardly, and distantly. But part of me always felt elsewhere. Dreaming. Waiting. Not dead, exactly, but dormant. I lived in a kind of Everworld of my own making—a secret place where I could imagine myself differently. I didn’t have the words for “transition.” But I imagined girlhood as something shimmering and unreachable, like Senna’s magic.

When I finally came out years later as an adult, it felt like surfacing into the world I had been waiting for my whole life, but it also meant leaving pieces of myself behind. Like the protagonists, I couldn’t bring everything with me. Some friendships didn’t survive. Some family ties frayed. But I moved forward anyway, because Everworld and other escapes had taught me that survival wasn’t about comfort. It was about transformation.

Part III: Senna as a Trans Icon

Let me be clear: Senna is not a trans character in any intentional or representational sense. She is not written as one, and the authors did not construct her story to speak to gender identity.

But art has a way of revealing what it never meant to say.

Senna is powerful. She’s manipulative, yes, but she is never powerless. She is blamed for things the other characters do not understand. She is feared because she refuses to be passive. She uses her body, her voice, her mind, as tools of survival and rebellion. And she is punished for it.

Senna is not likable. But she is unforgettable.

As a trans woman, I look back now and recognize something familiar in how the other characters treat her. They want to save her, kill her, tame her, or use her. They can’t decide if she’s victim or villain. But at no point do they truly listen to her. She is too dangerous to be believed.

Reading her at twelve, I didn’t know I was seeing a blueprint. But I was.

She was girlhood, reimagined as warfare. She was what happens when you tell a girl she’s too much for too long, and she decides to become a storm. She wasn’t the kind of girl the world protected. But she knew her power, and that terrified people. She was the first character I met who made me feel like being feared wasn’t the worst thing in the world. Maybe it was a form of survival.

In a sense, Senna’s story ends in tragedy. She dies. She’s consumed. But even in death, she shapes the world. The surviving protagonists inherit her ability to travel between realms. They become the new portals. The cycle continues—but it only began because of her.

She dies, but she doesn’t disappear. Her power lingers in others.

That, too, feels like transness to me. Not death. But legacy. The way trans people, especially trans women, especially the dangerous ones, especially the witches, change the shape of the world even when we’re not invited to stay in it.

Part IV: What Took So Long

I didn’t come out in my teens. I didn’t start HRT until much later. I didn’t know any trans people growing up. I didn’t even see a trans woman in media until I was already married in my mid 20’s, and even then, she was either the punchline or the tragedy.

By the time I came out to myself, I was already in my thihrties. And even then, I waited. I hesitated. I didn’t feel “trans enough.” I didn’t want to hurt the people who “knew” me. I was afraid of losing everything.

And for a while, I thought of that time as wasted.

But I don’t anymore.

I look back at that twelve-year-old version of me standing in a grocery store aisle, holding a book with a girl on the cover who was not safe, not kind, but impossibly real, and I understand now that my story didn’t begin when I started hormones. It began there. With that mirror. With that portal. With the ache in my chest when I realized I didn’t just want to be like her. I already was her.

The years I spent waiting weren’t empty. They were filled with stories. With reflection. With survival. With quiet rebellion. I was building a bridge to myself the whole time. I just couldn’t see it yet.

Everworld didn’t give me transness. But it gave me the courage to imagine another life. That’s the first step for so many of us.

Part V: The Body I Have Now

I’m writing this now as a post-op trans woman. My journey is still unfolding, but the terrain has changed. I’m no longer looking through the portal. I’ve stepped through.

That girl who read Everworld is still with me. She’s not a ghost. She’s not an origin story. She’s part of me. She was there in the recovery room. She was there when I filled my first prescription for estrogen. She was there when I looked in the mirror and saw something closer to truth.

Senna is still with me, too.

Not as a model. Not as a warning. But as an echo. A reminder of what it meant to carry power in secret. Of what it meant to live with one foot in another world. Of what it meant to be misunderstood, and still choose to exist anyway.

There are parts of me that still feel like a witch. Parts that still feel like a portal. I don’t always know what world I belong to, but I know now that I have the power to shape it.

Conclusion: The Portal Was Me

I didn’t know what I was doing when I picked up that book in Safeway at 12 years old. I didn’t know that I was holding the first thread of a tapestry that would take decades to weave. I didn’t know that the stories we love as children can sometimes be the maps we follow as adults.

But I know now.

Everworld wasn’t written for trans girls. But it found one. It found me. And it held me in a world where nothing made sense, but where I could finally feel something true.

And that’s the strange, beautiful magic of a story. You never know who it’s going to save.